By Emma Thomson

I hadn’t expected to feel like a movie star. But as our 4×4 manoeuvres past hulking boulders of black volcanic rock as big as cars, I half expect to see Anne Hathaway strolling around the corner in her Interstellar spacesuit, or Bruce Willis drilling away, as he does in Armageddon. So, can’t afford space travel? Come to Djibouti.

Bordered by Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia, Africa’s eighth smallest country sits on the Afar Triple Junction – meeting point for three of the Earth’s tectonic plates – and the result is a fantasy landscape of volcanos, petrified forests, desert plains, salt lakes and pristine coral reefs squeezed into an area one-sixth the size of England. Although it’s been in the news recently, due to its proximity to the conflict in Yemen, the British Foreign Office only advises against visits to the Eritrean border.

Exiting the fields of coal-coloured rubble, we pass through flatter plains where goats totter on their hind legs, hoofing the acacia trees and nibbling nervously around the pin-sharp thorns. Settlements of Afar people, with huts made of branches bent into a dome and a woven mat as a roof, stud the flat land. The end of “town” is marked only by a humble cemetery. The Khamsin wind, blowing in from the Sahara, whips the women’s colourful cloths out behind them like wings.

We drive towards Tadjoura, a gathering of square, white buildings on the north shore of the Bay of Ghoubbet. Its warm sapphire waters are speckled with plankton which bring juvenile whale sharks into the cove. My hostess at the seaside Le Golfe hotel arranges for a fisherman to take me out in his boat to look for them. He slings a couple of snorkels and fins into the bowels of the keel and we power away into the blue. I can’t make out his name amid the roar of the motor, but he speaks a little French so we try to cobble together a conversation. “Je suis un bon pilot,” he smiles, pointing to his chest proudly. I nod approval.

Deeper and deeper into the bay we go until the first signs of worry start to cross my captain’s face. “How often do you see the whale sharks?” I ask, a bit concerned now. “Quatre-vingts per cent,” he replies confidently – 80 per cent. The words are barely out before he’s pointing 20 metres ahead and shouting. I scramble to pull on flippers and a mask, and plop into the water feet first. There, right beside me, is a moving mountain dappled with snowflakes. I don’t want to harass, so I let him swim on but he turns and fins past me again – his small, bright eye looking directly at me. It’s just the two of us swimming side by side.

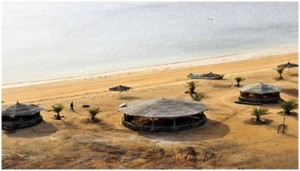

Just up the road from Tadjoura, a simple handwritten sign instructs us to follow a downhill track to Sables Blancs – a perfect hidden beach where a small, just-finished hotel on the shore awaits its first guests and, out front, a few grass-roof sun umbrellas sit in the sand. I wade in up to my waist and push my goggled face under and I’m shocked: shore reefs as healthy as this are rare indeed. Light-pink corals sprout from rocks, orange anemones do a Mexican wave and there are fish everywhere: triangle-shaped triggerfish with buck teeth, rotund puffers, rainbow-coloured parrotfish. I snorkel until sunset.

The next day, I drive back around the Bay of Ghoubbet to the briny waters of Lac Assal – Africa’s version of the Dead Sea and the lowest point on the continent. Its royal-blue waters are encrusted with clumps of sparkling salt crystals so white you have to screw up your eyes when the sun shines on them. A few hardy Afar men mine its shores and transport the salt to Ethiopia. They have built stalls from shards of flotsam, and balanced delicately on the planks are bags of hand-rolled salt and hand-moulded model deer heads for sale. It’s a hard life: temperatures can reach 47C. I take a bottle of water and hand it to the young son of one of the sellers. He smiles, takes my hand, drops a few salt baubles into my palm and curls my fingers around them.

My trip ends in the capital, Djibouti City. The outskirts are a terrible industrial sprawl of car depots serving the port, tin-can middens and plastic bags fluttering like flags from scrawny branches. But then you reach the Old Town – a colonial French outpost of wide, tree-lined boulevards and pastel-coloured façades. Pimped-out minibuses, with tassels trailing from their bumpers, ferry passengers to and from the market, where gaggles of women sit behind small mounds of tomatoes, wilting cabbage and fruit, or fan small ember-filled drums smoking fish. Meanwhile, groups of old men sit on the curb chewing the khat leaves that give a euphoric high, as they watch the world go by.

Near the centre is an ageing open-air Odeon cinema. Its chic Art Deco sign – cast in iron cubes – runs vertically down the side of the building. It’s not open any more, but as I look at the old movie posters peeling from the boarded-up walls, I’m half convinced I can spy the curling edges of an Armageddon ad. A fitting end to my mission into space.

Getting there

Emma Thomson travelled on Explore Worldwide’s (01252 883 764; explore.co.uk) 12-day Addis to Djibouti Adventure. From £2,459pp including flights and accommodation.

Red tape

British nationals require a visa. A one-month tourist visa can be acquired on arrival for US$60 (£40), but if travelling overland you must apply in advance. London has no Djiboutian embassy so apply via a courier service such as Visa Swift (visaswift.com), which costs £130, with handling fee.

Source: Independent.co.uk