By Said M-Shidad Hussein

Introduction

As the racial origin of ancient Egyptians had long been debated and searched from the Southern Pacific to southern Europe prior mid 1800’s, similarly the location of the ancient land of Punt, with which the Egyptians loved to deal and even identified themselves with, had also been a subject of debate among the scholars during that period. Champollion’s decipherment of hieroglyphs in the 1820s, which led solving the riddle on Egyptian origin, had also introduced the knowledge about the existence of historical Land of Punt and resultant investigation in the supposed places.

Although Champollion himself suggested that, on the basis of physical anthropology, Punt should have existed in the Horn of Africa, nevertheless the search on the location of Punt took nearly half a century looking for it from Syria and Yemen to Zimbabwe.

Although Champollion himself suggested that, on the basis of physical anthropology, Punt should have existed in the Horn of Africa, nevertheless the search on the location of Punt took nearly half a century looking for it from Syria and Yemen to Zimbabwe.

Eventually, from around the turn of the century onwards, many leading Egyptologists and other historians have recognized Punt in Northern Somalia through literary, anthropological, archaeological, ecological, and geographical accounts.[1]

But as it is usual that one may speculate about the location of that kind of important, but mysterious land, the precise location of Punt or its regional borders have occasionally been debated by some scholars, usually on inadequate ground. However, two arguments that have been made during the last two decades are quite different and it is necessary to deal with them here. Although the primary source of the first one is not available for this article, we will utilize an abstraction of it by a secondary source.

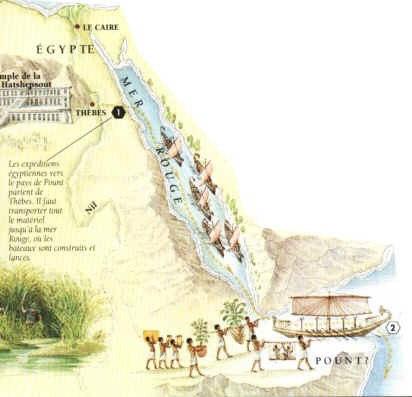

In the first argument, it is assumed that Punt was somewhere in Eastern Sudan, an area about 200 KM north of Khartoum. To make contacts with Puntites, it is added, the Egyptian travelers might have sailed along the Nile river, not by Red Sea, and then, at a point from the river, took an overland route to Punt.

The myrrh trees that were loaded onto Hatshepsut’s ships might show that they have been intended to replant in her temple at Deir-el-Bahri, “so that the Egyptians could produce their own aromatics from them … given the fact that such plants might well have died during the more difficult voyage northwards along the Red Sea coast”,[2] it is argued.

Traditionally, it has been believed that the Egyptians were travelling by Red Sea from the ancient ports Marsa Gawassis or Quseir. Contrary to the argument, new findings have affirmed the validity of that assumption. A well preserved remains of large ships and harbor installations such as “ship’s timbers, anchors, coils of ancient rope, and the rigging of seagoing ships that date from the reigns of several Pharaonic dynasties” are excavated from the port Marsa Gawassis.[3]

Additionally, a major expedition was sent from that port, which is close to the western end of Red Sea, by Pharaoh [Amenemhat IV] about 3,800 years ago.[4] Kathryn Bard, a Boston University distinguished Egyptologist, led the excavations and has subsequently announced: “We have made a wonderful find there. It was really amazing – 40 cargo boxes from the ship, and some were inscribed with the name of that very king, the name of the scribe, and the inscribed words, ‘wonderful things from Punt’.”[5]

Among many other evidences, the findings from this port in general and the relics of the expedition in particular, eliminate the possibility of a route along the Nile to Punt. One cannot see any reason to entertain that assumption anymore.

The second argument is based on a case study of two mummified baboons that were taken from Punt to Egypt which are now held by British museum in London. The study has been conducted by two other scientists: Nathaniel Dominy, an ecologist, and Gillian Moritz, a specialist in a mass spectrometer in the Dominy’s laboratory. The ecologist has sheared a few hairs from the baboons for the lab specialist to work on, for a purpose of using “baboons as a lens to solve the Punt problem”. Describing it as “a complicated bit of chemistry”, David Perlman, Chronicle Science Editor, who has appreciated the study explains:

“Despite their age, those hairs still contained trace molecules of the water the animals drank when alive … every oxygen atom is made up of three different stable isotopes-their atomic masses- and the ratio between two of them, oxygen-18, varies significantly in the rainfall and humidity from one part of the world to another, even from different parts of a continent.”

He continues: “Moritz used… ratios in the hairs of each mummified baboon, and compared them with the ratios in all five species of baboons living in varied parts of Africa today.”

By this, the researchers have come to believe that the habitat for the type of the baboons in question lie on both sides of the border between the Ethiopian-Axum and Eritrean-Asmara regions, which shows that it is “the place to look for punt.” Moritz said.[6]

The view might remind us of one opinion expressed by some scholars in which they look for the origins of the queen of Sheba from the very same region. Uncertainty, however, is expressed within this assumption for the land. Notwithstanding her findings from Marsa Gawassis, Bard proposes that Punt may have also existed in a similar confronting baboon area of eastern Sudan.

Judging from what it is given, it is doubtful if one can be convinced that there are now more answers than questions. Former Egyptologists have taken into account the type of ecology for Puntite baboons taken to Egypt.[7] They have found that their ecology belongs to the rocky hills along the coast of RaasCaseyr-Jabuuti (Cape Guardafui-Djibouti) region which was known by Egyptians and Greco-Romans as the Aromatic land.[8]

Does this mean that a reconciliation between the two findings is required? Since the Sudanese area is not initially considered into the study does this indicate that the baboon question is yet to be exhausted?

If Punt was in northwestern interior region of the Horn of Africa, why had the Egyptians required to travel thorough uneasy journey to a relatively remote inland while they could meet their demands on the Eritrean coast? Even if the most of the interactions had been occurring on that coast, why had these ambitiously-organized voyages been limited to unpromising destination while they could reach out the nearby Aromatic Land, the real field of their primary demands; or why is not possible that they could pick up a sort of these demands from the former during some of their returns from the Aromatic Land, northern Somalia?

Why could they sail over the most difficult part of the Red Sea (today’s Red Sea) but they could not do so over the more Pacific remaining part of it (today’s Gulf of Aden) on the Aromatic coast? In another word, which one was easier for them to take the overland route to Asmara-Axum area or to continue the voyage to places like Zailac (Zeila), Berbera, or Xiis which produce aromatic resins with higher quality and quantity? In fact, while it was not even a concern previously, the new findings prove that their maritime technology could enable them to sail to farther places such as Raas Caseyr for the best and the biggest kind of these products.[9]

Feeling the hasty nature of the statement and its lack of adequate strength to cause departing from the widely accepted idea of looking for Punt from Somalia, Raphael Njoku has newly noted:

“Further studies are needed to conclusively affirm this new finding on Punt’s location. Until then, the previous inconclusive but strong evidence is still relevant and worthy of consideration.”[10]

Other researchers who have also published their work recently do not find a reason to depart from that old idea.[11]

Dr. Njoku, a world-class writer, a history professor, and the director of the international studies program at Idaho State University, also asserts the historical importance of Somalia’s trading links with the ancient leading civilizations and the nature of its exports through the trading city-states along its coast, well known through archaeology and Greco-Roman records. As such, he reminds us: “the coastal city-states produced and traded significant amounts of the precious goods that were associated with the people of Punt.”[12]

The scholar must be right. One finding isolated from many others cannot change the course. It is noteworthy to remind also that the historiography on the Horn of Africa suffers a lot with snagging or selective approach in the studies which results an absence of authentic identity, or what Legesse Asmarom describes as an “erroneous conclusion” by a selected “narration”.[13]

As we have mentioned, scholars have previously calculated and based their findings on the types of the products; trading history of the region; the distance and requirements of the expedition to the land; and some archeological, environmental, linguistic, and cultural accounts. The types of the commodities, particularly the plants, have been the subject of the special interest.

In this study, on the basis of unequivocal linguistic evidence; genetic accounts; and intimate review over the previous observations, it is conclusively almost secure to declare that Punt have existed in northern Somalia and to stay on the view for that in the former studies.

The purpose of this paper is to show how this is not a premature conclusion. In the remaining parts of the paper we will discuss, one by one, about the nature of Egyptian imports and prehistoric trading conditions of Somalia; continuation of its commercial status; linguistic evidences; ethnographical significance of Puntite names; a biological factor; cultural connections; archaeological clues; and the nature of many historical names for the region as an aspect of great ‘x’ vs. proper ‘x’, for example greater Horn of Africa vs. Horn of Africa proper.

Part Two forthcoming

Email:[email protected]

———————–

[1] See Part 2 & Part 3 forthcoming.

[2] Ian Shaw, 2000, Egypt and the Outside World, in Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, p. 317.

[3] David Perlman, May 2010, Scientists Zero in on Ancient Land of Punt.

[4] Apparently not Amenhotep of Perlman’s article. The three Amenhoteps, 1451-1349 BCE , belong to the New Kingdom, so this must be Mentuhotep IV, 1992-1985, or Amenemhat IV, 1786-1777.

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid.

[7] Herman Kees, 1961, Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Topography, tr. G.H. James, p. 112.

[8] See part 2, forthcoming.

[9] Lincoln Paine, 2013, The Sea & Civilization: A Maritime History of the World, chap. 2.

[10] Raphael Njoku, 2013, The History of Somalia, p. 30.

[11] Bob Brier & Hoyt Hobbs, 2009, Ancient Egypt: Everyday Life in the Land of the Nile, pp. 30, 157.

[12] Njoku, The History of Somalia, pp. 29-31.

[13] Legesse Asmarom, 2000, Oromo Democracy, pp. 2, 4.

We welcome the submission of all articles for possible publication on WardheerNews.com. WardheerNews will only consider articles sent exclusively. Please email your article today . Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WardheerNews.

WardheerNew’s tolerance platform is engaging with diversity of opinion, political ideology and self-expression. Tolerance is a necessary ingredient for creativity and civility.Tolerance fuels tenacity and audacity.

WardheerNews waxay tixgelin gaara siinaysaa maqaaladaha sida gaarka ah loogu soo diro ee aan lagu daabicin goobo kale. Maqaalkani wuxuu ka turjumayaa aragtida Qoraaga loomana fasiran karo tan WardheerNews.

Copyright © 2024 WardheerNews, All rights reserved